Cheer for the banner as we rally 'neath its stars,

As we join the Northern legion and are off for the wars

Ready for the onset, for bullet, blood and scars!

Cheer for the dear old flag!

Glory! Glory! Glory for the North!

Glory to the soldiers she is sending forth!

Glory!Glory! Glory for the North!

They'll conquer as they go!

1861- Fourth Battalion of Rifles

13th Massachusetts Volunteers

Chapter

3

A

Perennial Malignancy

God

bless her, Mary thought. Mariah was right about everything.

But wrong about her assumptions. Given her perspective, she could not foresee the infinite difficulties. Imminent

Abolition was not acceptable! Not feasible. The Southern agrarian

economy was based at its core on affordable slave labor. The Southern

investment in purchasing and housing its slaves was made under the

assumption that it would be returned over years of labor in

the cotton industry. A sudden loss of that labor and the investment

it represented, and huge, immediate increases in labor costs would

shut down the economy of a dozen states- and their farms and thus

their crops and eventually their banks. Abolition was tantamount to

social collapse and economic failure... on epic proportions.

An army was gathering across the Potomac, regardless of Southern excuses, and northern American patriots sang confidently of their superiority... morally and militarily, threatening to invade, sure of their righteous cause, and most importantly their loyalty to "the North."

They had conveniently forgotten, or perhaps they never knew, that human slavery had been the law of the United States for a century; that the North had been going through a religious revival and become radically self-righteous in recent decades, and Northern slaveholders, under great social pressure, had been divesting themselves of their slaves for years... sometimes freeing them, but just as often selling them off... transferring their shameful equity southward, into the agrarian South.

Northern businessmen had successfully cleansed themselves, and joined the groundswell of condemnation against the slaveholders in the South. The "North" had suddenly become a bastion of Christian love and humanity, and was determined to expunge the very labor force which had built the country, and readily conveyed their sins to the South, forgetting their own. Once the North had largely divested, their rush for Abolition was on. They had the will, and a President who would organize an army, and a Media who would make the whole campaign a glorious enterprise.

The soldiers began to sing and raise their spirits to their task. They believed, had been convinced, that God would be pleased, if they were to turn their guns on their own countrymen, and to kill any Americans who stood against them. It was the North's duty to cleanse the continent. The United States of America was no more. The "Union" became the North, and the North was on God's side.

Not America, but the North. They did not sing of an American legion, but a "Northern Legion." The press and the politicians had completely programmed the Union army to think of a provincial, regional identity as it threw itself into the jaws of death. Many thousands were glad to volunteer, from the Northern states, ready to fight and die, for a supposed Northern cause. Already relishing in their assured victory and ultimate "glory," they assumed the South was soft and morally weak, and would flee when they saw their bayonets glistening on the road to battle.

This Northern army had no illusions about national unity, or any sense of brotherhood with the southern states. That had been destroyed after years of demonization of Southerners, by fires of hatred ignited by many politicians and publications trying to shame the South into reform. The common Northern soldier was putty in the hands of the Abolitionists, who convinced them they were doing God's bidding. Southerners had become a contemptible enemy, deserving the most radical kind of punishment. Northern volunteers were ready to lay down their lives for such a cause, and John Brown, the radical Abolitionist and violent insurrectionist, had become their patron saint.

Mary was overwhelmed with the changes in the country, in her social status, with the threat of a civil war, and the choices she and her family had to make soon. Slavery

was evil, and

it was time, perhaps past time to end it, and her father had known

that... Many slave owners had begun the process of transition... but

many more Southerners, newly invested, talked as if Abolition was out

of the question. The pervasive sexual exploitation of many thousands

of negro woman by slavemasters guaranteed a class war to the last guilty man.

What Mariah foresaw was out of the question as

well... Blacks and Whites at the same table, sharing the same class

in society? Her own boys scaling and cleaning her Black nephew's

fish!...

This

was delusional prophesy by an ignorant person; it could never, should

never be. The Southerners like the Custis family had been generous as it was,

constructing a second tier for some blacks- of patronized but limited

opportunity. But they could never be equals.

Washington,

Jefferson, Jackson, now Lincoln, none of them ever foresaw “equal

rights,” or conceived or planned for Mariah's vision of America.

White America had been very short-sighted, created with

blinders on, just as Mariah said. A Republic built on human rights, which

condoned Slavery! What cruel travesty and national

schism had the founders left her and her fellow Southerners to

contend with? The idealism of the "Founders" now seemed so hollow compared to

the rumbling volcano which was about to burst.

And now either way, two plagues were

unavoidably descending on the South. It was either bankruptcy and humiliation

for most farming families, or social chaos and perhaps racial conflict for

the whole country. And the only way to head off that disaster was for a

showdown... a civil war to settle things; where the North would supply Federal

troops to do the fighting for the slaves... then probably ignore them as they

had done the Indians and most immigrants to the frontier. It was

madness, tantamount to a huge, impoverished class. Abolition may have

been justice, but its cost would not be. How could a war, the killing of each

other, perhaps by the thousands, and the destruction of the South be more

righteous than slavery? The judgment and imposed suffering aimed at the South

was enough by itself to inspire rebellion. What men on earth would just give up

and abandon their culture and their economy, and choose poverty because people

somewhere else do not approve of them?

The Republicans

had no plan beyond Emancipation. Who

or what would pick up the pieces? How much harder would it be

after a war, God forbid, to do so with freed slaves, a huge portion

of the Southern population suddenly adrift, indignant, yet penniless

and vulnerable to political and commercial manipulations? Crooks and

flim-flam men would have a field day. In many communities, the Negro

population was almost equal in number to the Whites. Freedom... and

something even more dangerous, VINDICATION, could inspire

revenge crimes and even race massacres all over the South. And

Negroes, like any oppressed people, could be emotional and even

violent when provoked. Crime and unrest was bound to explode as freed

Negroes became hungry and desperate. They might even need protection

from themselves.

Were

the Federal Government or the Abolitionists going to provide the

Negroes with homes, and jobs and many other requirements for

survival, until they adjusted to their newfound freedoms and

responsibilities? Of course not, no matter what people said. At

least with slavery they had some Southern advocates who understood,

and really cared about the Negro's welfare, and their eventual

acculturation. In fact the Negroes were in many cases

blood-relations, and what Southerners needed was time and reflection

to face the reality that they had inadvertently created a sub-culture

of kinsmen- with no legal rights or inheritance, but for whom justice

would demand better. Mary believed that most of them would respond just as her father had. And it would be a beginning of freedom, and for some freemen, a gradual rise in social status.

Rights

for them would eventually mean rights for all Negroes. But it would be delicate

negotiating... and it would take time... and many Southern families

would want privacy in these settlements. Lincoln could not just wave

a magic wand and make the problem go away. He was only making the

problem worse.

Central

to the American experiment was the right of men to manage their own

affairs, within the laws of the land. No small amount of Southern

pride was being insulted, enraged at the idea of laws being changed,

one region judging another, taking authority over it, and then dictating

commerce policies which would ruin them. What about their

Rights?

Mary

suddenly realized that for all of his faults, her father had been

far-sighted, quite progressive, being so generous towards the

Negroes. Regardless of the whole family's great loss, he set the date

of eventual emancipation for his slaves in his Will. For decades he

had violated the law, in fact all of them had, preparing the Custis

slaves for eventual freedom, by routinely teaching many of their

slaves to read and write. And they had taught them discipline and

responsibility by trusting some of them to set up a vegetable market

in Washington City, all by themselves. The slaves oversaw the

harvest, set up the vegetable stand, handled the money, and took care

of minor expenses. They could come and go at will, sign receipts for

their master, were trusted to convey important messages, and were at

times depended on to practically run his various business ventures.

And the symbiosis did not stop there. It was an interdependent

community, where everyone worked together in the gardens and fields

and shared the fruits of their labors... and they had once even worshiped

and thanked God for this bounty under the same roof.

Whether

just feeling guilty or belatedly good-hearted, Wash Custis had

fashioned a prototype of the future Southern plantation, years before

it would be politically expedient, but right on time as events were

unfolding. In fact slavery might be similarly transformed- tolerably

mitigated, but it could not be abolished instantaneously without

tremendous hardship for all concerned. People who did not live with

the problem of slavery could not imagine the mayhem that would be

caused by emancipation. And it might take fifty years to sufficiently

acculturate and enfranchise the Negroes.

Slavery

was wrong, a social evil, but it was the only system at the moment

prepared to guarantee the feeding, housing and productivity of a

cruelly transplanted sub-culture. Going back to Africa was an absurd,

abandoned alternative. With Abolition, at best the slaves would just

become migrant farm workers; but bound by immobility and ignorance,

still largely dependent on the plantation economy, which would no

longer owe them any paternal oversight. Emancipation would require equity... a

doubling in every community in infrastructure; Schools, roads, law

enforcement. These were concerns, perhaps understood only by the

slave owners, which had prohibited or postponed emancipation long

before.

Freedom

and Rights for Negroes would surely come... as the South went through

the same social revolution experienced by the North. That was an

often ignored but inescapable fact. Enough Blacks were free in the

United States to be able to prove their ability to adapt and

contribute in a greater way to society. And some were children of former Arlington slaves. The seeds of freedom were

already planted. And all of the tenets of Christianity demanded it.

All the South needed was time.

But time had run out.

Abolition

on the other hand, whether accomplished by mandate or by war,

would only create millions of freed slaves with few lifestyle or

career options, and no homes and no place to go. Negroes were prisoners of a cruel

fate and a horrible American tradition, but they were valued-

considered valuable possessions to many families, essential assets to

many farms and the whole Southern economy. In the end, they would be

considered worth dying for. Even worth killing for.

Thanks

to sensational publications, such as Uncle Tom's Cabin, the

Abolitionists had painted a very different picture, of teaming

wretches, whipped and damned, horrifying the North and inspiring

extreme action. But for a majority of Blacks, a war would only change

legal, regulated bondage for something worse; a random, endemic

bondage to poverty and persecution. Was that change of terminology, a

mere technicality with tremendous implications, worth killing- or

dying for? If so, then how many would die and lose everything? How

many, before the cost of Abolition, in blood and treasure, was worse

than the evil it sought to end? The country seemed determined to test

that question.

The

so-called United States had changed, and grown distinctively away

from the compromises understood and tolerated by its forefathers.

Ironically, now an intolerant “Union” made demands of radical changes that

Southerners could not meet. "Old Virginia," The America of George Washington and

Jefferson had fallen into disrepute. Forsaking the American founders and

their delicate compromises, the Unionists were forcing acquiescence or disunion, and risking all-out war. Soldiers like Colonel Lee, who loved the country, who had served it all of their professional lives, were suddenly asked to enforce a Northern-based social movement, and dispense with the established compromises made by the American forefathers and the United States Constitution, and to be willing to override States Rights, abandon their own personal fortunes, all of which had been legal enterprises, and be willing to take many human lives to obtain complete Abolition. They saw the prevailing powers in Washington as traitors to the American foundations of civil discourse, self-determination, private property, State autonomy, and other issues. But it was the South which would be branded as traitors, and some day require "Reconstruction."

The

carriage turned up and on to the main, well-worn road to the

Arlington mansion. Mary was ready now to consult her beleaguered

Colonel, about the most important decision of their lives. Whether

Robert answered the call of his country, or his loyalty to their

fellow Virginians, there was surely going to be war. And it just

might begin in their living room.

//

“ //

Most

Americans don't really give much thought to George Washington.

His achievements have become like those of a biblical character,

distant and even dubious. And most Americans feel like they know all

anyone needs to know about the “Father of our Country.” The

embarrassing reality is that Americans know very little about the man

staring up at them from the dollar bill, or whose stately profile

adorns every American quarter, the man who led our forces in the

Revolutionary War, the rebel cum visionary countryman who refused to

be our king, and helped to fashion our Republic instead. But to not

investigate or understand Washington is to do the same for the Lees.

One was truly the progenitor and inspiration of the other. Regardless

of the tradition of thinly veiled contempt for Robert E. Lee among

many Americans, he was a great American, in the highest sense of the

word, and would have been approved wholeheartedly by Washington, his

legendary, distant in-law.

Ironically,

the father of our country never had any children of his own,

but he had step-children. And thus step-grandchildren... including

one male whom he adopted upon his stepson's death, who in turn made

his own home an iconic monument to his esteemed step-grandfather, a

palatial landmark overlooking Washington City in the distance, called

Arlington. His name was George Washington Parke Custis. An artist,

poet, historian, playwright, statesman, civic leader and father of

Mary Anna Randolph Custis, in whom he poured all of the Washington

legacy into, from the day she was born.

Not

surprisingly, Mary Custis was easy to understand, a Southern belle

born into prestige and privilege, who embraced all the trappings of

her heritage and culture, and attracted notable suitors, in spite of

her lack of beauty or wealth. Sam Houston once courted her, when he

was a controversial Tennessee congressman. She was attractive because

of her charm and conversation, a fun, lighthearted personality fed by

“good breeding” and intelligent parents, and backed by a mountain

of status as the girl raised by the grandson who once sat on the

hallowed knee of George Washington.

Mary

was just the kind of wife a West Point cadet would desire to embolden

his resume. And when her recently graduated cousin, Robert E. Lee

posed the question, there was no hesitation. Lieutenant Lee was just

the kind of man who would reinvigorate the Washington and Custis

line, and bring handsome children into the Arlington estate.

Lee was the son of another hero of the American Revolution, one of George Washington's favorite generals, Lighthorse Harry Lee. There were few Americans whose heritage was more stellar, or whose patriotism more bona fide than these two young American patriots. But Mary's father was not so sure of Lee's fitness, preferring she marry someone with a much larger financial portfolio. Slave labor was an inefficient resource, and as Arlington's slave families grew, they became an insatiable sponge. Custis was “rich,” but land and slave poor. Arlington plantation was starved for cash flow and desperate for upgrades. “Wash” Custis, as his admirers knew him, was a popular Washington City fixture, but had never had the knack for business, and had not sold off enough of his slaves to maintain his profits. Many of his slaves were old or infirm, or too young to aid productivity. He was probably attached to them and feared others would not treat them well, but meanwhile they were eating nearly everything he could raise.

Custis's grandiose Arlington dream, the monument to President George Washington, had stagnated, become a classic example of the law of diminishing returns. There were constantly more mouths to feed on a farm with limited productivity, the whole place was beginning to show marked depreciation, and yet the second floor of the mansion still had never been finished. Custis's needs were far more serious than the young, landless, West Point officer could sustain, and his daughter was his last ace to play. Robert E. Lee was not a suitable suitor.

Lee was the son of another hero of the American Revolution, one of George Washington's favorite generals, Lighthorse Harry Lee. There were few Americans whose heritage was more stellar, or whose patriotism more bona fide than these two young American patriots. But Mary's father was not so sure of Lee's fitness, preferring she marry someone with a much larger financial portfolio. Slave labor was an inefficient resource, and as Arlington's slave families grew, they became an insatiable sponge. Custis was “rich,” but land and slave poor. Arlington plantation was starved for cash flow and desperate for upgrades. “Wash” Custis, as his admirers knew him, was a popular Washington City fixture, but had never had the knack for business, and had not sold off enough of his slaves to maintain his profits. Many of his slaves were old or infirm, or too young to aid productivity. He was probably attached to them and feared others would not treat them well, but meanwhile they were eating nearly everything he could raise.

Custis's grandiose Arlington dream, the monument to President George Washington, had stagnated, become a classic example of the law of diminishing returns. There were constantly more mouths to feed on a farm with limited productivity, the whole place was beginning to show marked depreciation, and yet the second floor of the mansion still had never been finished. Custis's needs were far more serious than the young, landless, West Point officer could sustain, and his daughter was his last ace to play. Robert E. Lee was not a suitable suitor.

Wash

Custis, and his daughter Mary- and Arlington needed an experienced

planter, not a rootless soldier. Lighthorse Harry had been a worse

businessman than Custis, leaving his widow in dire straits, so Robert

E. Lee had few assets. Custis delayed the couple, hoping their

romance was only an infatuation, but he eventually relented, always

embracing compassion over feasibility, as his daughter's happiness

came second only to his own. And his mercy was rewarded.

With

Lee's various military assignments, daughter Mary would call

Arlington home more often than not, which pleased him very much. Wash

Custis would enjoy much of his last days enjoying Lee's modest but

faithful injection of funds and sound management, and surrounded by

his invigorating and loving grandchildren. When he passed, he had the

comfort of knowing the Arlington mansion was being restored; his

family was in good, sound hands; his grandchildren would spend their

days frolicking among the rose gardens of Arlington, and his many beloved slaves would soon be set free.

Strange

that such noble aspirations and a hopeful American narrative

could conclude so far from its conception. But little of his scheme

transpired like Wash Custis planned. In fact little transpired like

anyone planned. A social revolution, a congressional miscalculation,

and a dysfunctional election propelled the Southern people into a

tragic defensive action, and suddenly the idyllic Lees were astride

the merciless blade of a national sword which would divide the

nation. It would not only spoil Custis's Utopian scheme, but cost

many Americans their fortunes, the American government its

international prestige, and nearly a million Americans their lives.

And the Lees would lose everything.

To

this very day, Americans who study the Lees wonder, incredulous, how

did Robert E. Lee decide which way he would go? Considered one of the

great American military minds of his generation, imbued with a great

love for his country as evidenced by three decades of military

service, with everything to lose if he chose to support the Southern

cause, what personal convictions could possibly have inspired Lee to

join a revolt?

Colonel

Robert E. Lee, the son of a hero of the American Revolution, who

married the great granddaughter of the “Father of Our Country,”

and lived in the very monument and museum to George Washington- Why

would a lifelong patriot risk or sacrifice this sterling reputation,

a grand home and the safety of his family, and even his life?

Staying

the course would have meant a much safer and vastly easier course,

and the assignment offered him by President Lincoln, as Major General

over defense of the very Capital of the Nation, was perhaps the most

enviable in the United States Army. Empathizing with Lee's reluctance

to fire upon his fellow Virginians, Lincoln and his cabinet might

have thought the offer the most humane, and yet beneficial to

themselves. But Lee chose the Southern Confederacy, to everyone's

dismay.

Had

Robert E. Lee gone the other way, stayed in the Union, and

combined his genius with the North's superior resources, it would

probably have been a very short war. Certainly those on both sides

believed that it would be anyway. Slavery would have been greatly

curtailed and eventually stopped, Abraham Lincoln might not have been

assassinated. Richmond, Atlanta and other Southern cities might not

have been destroyed, and millions of lives might have been spared.

The South would never have suffered the destruction and loss of

capital and manpower that it did, and the Lees would have kept

Arlington, and lived there happily ever after. Even if very poor.

If

only Lee had been able to ignore the ominous bullying of the North,

and the Northern agenda of an extreme federalist America, which

seemed to have no limit of lust for centralized power. If only he and

his wife had not grown up in the shadows of George Washington, who

had not only brought independence to America, but a national unity

based on compromise between federalist ambitions and republican

suspicions. If only.

Washington

and Lighthorse Lee and others had agreed to the Constitution and

basic federalism to avoid civil war and anarchy. They had balanced

the federalists scheme with the Bill of Rights, which was thought to

insure States Rights. Now that balance was hopelessly askew.

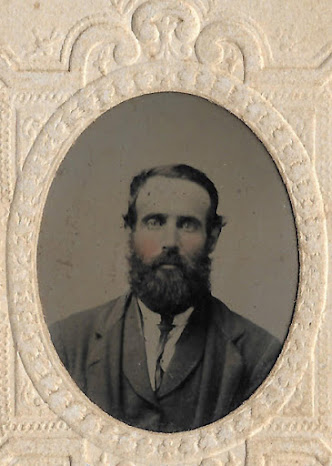

Young Custis Lee, the oldest son, about the time he was enrolled

at West Point Academy. He would become a general

in the Confederate Army.

Mary

and Robert Lee's seven children waited in suspense to learn what

would be their fate. His oldest two sons were already proudly serving

as soldiers in the United States Army. One daughter was nearly

engaged to an American officer on General Winfield Scott Hancock's

staff. His oldest daughter Mary already lived across the “Mason-Dixon

Line,” in the North. His brother Sidney was a U. S. Naval captain. And Sidney's

sons were also in the military. It was all unimaginable, all those

West Point cadets they had loved and watched through the academy,

graduating... also having to make similar choices.... and no doubt

ending up at war against each other!

Rooney Lee, also enlisted in the United States Army,

would resign his commission and join his father and

brother... and lose his health, his wife and his children

during the war.

Mary

sat silent, afraid to speak. She had to prepare for either

possibility. Eyes all over the room were watering the floor. She knew that Robert

loved America. He would honor the memory of his father... and Mary's

step-great grandfather... he knew what he must do... the slaves were

about to be free anyway... Soon they would own none. If the Union was

worth dying for, and Robert had always been willing, it was worth

more than one man's assets anyway... There was no other country for

Mary, America was in her blood... Her father's... They were

America!

Robert E. Lee Jr. was in college but would

eventually join the Confederate Army.

Then

Lee appeared, distraught but resolved. He horrified his family as

they listened, and he had chosen the South; to him, the America he

had always been fighting for, the one in his head, and perhaps the same

one that had been in George Washington's and Lighthorse Harry's

heads, even before it existed, called him. And it was, after one

hundred years, best represented by his home state of Virginia.

The women cried... disbelieving... devastated, and yet willing to serve their family and their country however necessary.

The women cried... disbelieving... devastated, and yet willing to serve their family and their country however necessary.

Mary the oldest daughter, would flee to stay

with close friends... safely in the North.

The

Lees had to abandon their Virginian empire and soon enough, George

Washington's belongings were rifled and spread by the winds of war,

and Arlington plantation was ravaged and made into a prominent

government graveyard. The name Lee was made the equivalent of traitor

and "slavocracy." And the slaves at Arlington? By the end of the war,

they had already been set free according to Wash Custis's wishes, as

stated in his will.

Annie, second oldest, was blinded in one eye

as a child. She would not live through the war.

What

was Lee thinking? Mary's heart was already in tune with her

father's and slavery was not in her or Arlington's future. If

necessary, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington could just

move across the river and be a celebrity, until hostilities ceased.

The slaves were more like adopted family, some were family,

soon to grow up and leave.

The

Lees loved their country. The answer was obvious. But not so obvious

to a Constitutional scholar, or a believer like Lee.

Robert

E. Lee knew that regardless of the political rhetoric, or

Abolitionist propaganda, what the North was doing was predatory and

contradictory to every covenant so painfully achieved by George

Washington and others. Now the Lincoln Administration had asked him

to help lead the army that would subjugate the South by force, and

begin the inevitable dismantling of the Southern economy. The “brass”

hoped, even assumed that as a good soldier, Lee would do whatever he

was asked; Even betray his own Virginians, even shed some of their

blood.

Shed

blood, and it would take a lot of it, from Washington to Texas,

perhaps kill thousands in the end, hopefully not, but however many,

trade the lives of free, law-abiding, American citizens for an

unplanned process to end slavery and bankrupt half of the country. To

Northern radicals, the horror of the killing of fellow Americans was

somehow considered preferable to the horror of slavery, which was

still the law of the land, even in some Northern states. Lee saw it as madness.

Never

the less, Robert E. Lee would never be able to forget General

Winfield Scott Hancock, a great mass of blue adorned with gold

buttons and braids, beseeching him to take the helm of the defense of

his country. It was a just cause. The Union must stand. It was God's

Will. President Lincoln would not back down, there was a limit to

“State's Rights.” And especially Secession- although

theoretically legal, it had to be discouraged. Else the whole Union

would turn to dust... A grateful country would be forever indebted to

him.

Slavery,

the cause of the whole stink, should and would finally be ended in

America. When Lee handed in his resignation instead, Hancock told him

it was a great mistake he would live to regret. Lee already regretted

it, but he had not created this schism of intolerance, whose appetite

could only be satiated by a war.

Robert E. Lee

proved a popular axiom about soldiers; that most soldiers fight for

home, their loved ones, their buddies in the trenches with them, not

the government or abstract ideas like causes or social movements.

Freedom,

not Slavery was the main issue for Lee. Personal autonomy. And

the assurances made almost one hundred years before to General

Washington, who worked so tirelessly to prevent an internal war

between Americans. Lee's father had been almost killed after the

Revolution by political hotheads, determined to incinerate a

newspaper office, totally unconcerned with the “Freedom of the

Press.” Angry, self-righteous mobs, or government use of brute

force, were not what was intended by the founding fathers. Bullying,

intolerance and oppression had been exactly what brought the

Pilgrims to America. Our freedoms, of Religion, of Assembly, of

Speech, of the Press, might become just as inconvenient or

unimportant to the Lincoln Administration as State's Rights. [And they did]

The South had

its rights, for Southerners to live according to their own

consciences... their religion, even if that Faith was somehow compromised;

America was nothing if not the Freedom to practice one's beliefs,

within the laws of the land, even if they were also imperfect.

The

loss of charity towards one's countrymen, over perceived

rights or wrongs, meant the “Union” was already lost. The

willingness to use military force on her own people was in fact abuse

of it. The only kind of Union worth dying for was one comprised of

willing members. It was the Moslem hordes who demanded compliance

under the threat of death. President Lincoln's stance was abhorrent.

A

good soldier never questions the laws, or the borders, or the people,

he just obeys orders and defends them. That sometimes requires great

trust in the system, and the resolve to die if necessary, for things

one does not necessarily completely understand. But, high up in the

military and connected with the Washington City grapevine, Lee did

understand. The people, and the laws, and the borders of Virginia had

not changed significantly in many years. Nor had most states in his

native South. They may have needed to change, but they could not be

forced to, and none of them deserved to die for modern

interpretations of what George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, and

Harry Lee had carved out of a wilderness and made into a country, and

established laws, which had survived for nearly one hundred years.

Oppression

and the threat or use of war to settle regional differences in the

so-called Union was an unacceptable, disillusioning precedent. It was

not something worthy for an American patriot to die for. In fact, for Robert E. Lee, the only honorable option was standing against those things.

If

American states could be penalized, or American citizens could be

vilified and vanquished or rendered to vermin because of their legal

activities, then Freedom and “America” no

longer existed as it was conceived, it no longer deserved defending,

and the Confederate States had every right to secede and draw up

their own government.

If

there was going to be a war, Robert E. Lee was going to go

down on the side of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights as

designed and endorsed by patriots like his father. The Northern

bullies deserved their comeuppance. They could not whip the South, or

even scare it. They would back down when they saw the thousands of

Southern rifle barrels aimed at them, ready to defend their farms,

their families, their way of life. [And they did] In fact by joining the South, he

would probably save lives. So he hoped.

When

all of his Unionist ex-students from West Point, now leading

battalions, saw him and other military mentors across the

battlefield, flashing their sabers, they would probably refuse to

fight. It would be a shorter conflict with Lee wearing gray, and calling the "Union's" bluff. And then

all of America, some a little chagrined, could return to the Red,

White and Blue.

It

was perhaps the greatest miscalculation, with the worst consequences,

accompanied by the most personal sacrifice, in American history. Lee

could not have made this kind of decision because of treason or

racial hatred, but purely as the only choice he could make and keep

his own self-respect, as an American, in the classic sense of the

word. Not for personal gain, or glory, in fact the opposite. When he

told his aching family that he would resign his commission in the

U. S. army, the tears gushed, and yet they supported Robert E. Lee

with an overpowering trust in his wisdom. And quickly their world

went into a blur of confusion, displacement and destruction. Mary sat

in shock, unable to conceive the gravity of his choice, but fearing

their blessed, idyllic life had just come to a scandalous end.

All

three of her sons would also enlist and fight for the Confederate

States of America. As would Lee's brother and nephews, and Agnes's beau. Robert E. Lee would become recognized as one of the greatest

generals in human history. But the North did not repent. It stammered

and procrastinated, and changed commanding generals several times,

but it fought with Yankee resolve, often losing men disproportionately to the South. Lee's Virginians would fight

courageously, along with a dozen more states, routinely trading two Union lives

for every Confederate one, until they were barefooted and throwing

rocks. But they would be beaten by the deeper federal pockets, which

could arm and feed overwhelming numbers of soldiers, daily

conscripted on her shores as they immigrated from Ireland and

Germany, and could manufacture their own munitions, and keep a far

superior navy afloat.

When

the terrible civil war was over, the Lees had no home to go home to.

Vindictively, during the conflict, General Lee was singularly

persecuted by Federal authorities. Based on unpaid taxes, the whole

Arlington plantation had been confiscated and commandeered by the

United States Government, via a legally shaky condemnation and sale.

Conveniently located in sight of Washington, the farm was then

utilized as a giant cemetery for Union soldiers who had been killed

in the conflict. A large government housing project for hundreds of

freed slaves now shined in the sun, segregating blacks from Washington proper, and insuring that the Lee's home

would never be easily recovered. Union officials ignored the

illegality of the confiscation and improvements, and instead saw it

all as poetic justice.

The

Custis-Lee mansion stood hollow and neglected, and the Lee's

possessions scattered in several places, and some of the relics of

George Washington requisitioned and placed in the U. S. Patent

Office. During the war, daughter Annie had perished, as had son

Rooney's wife and both of his children, and his home was

unnecessarily burned to the ground. No doubt the whole country had

similar losses and died a little, and shared a national depression,

which was part of the reason why Lincoln and Grant chose such a

merciful treatment of the conquered “rebels.” They had been

sufficiently punished. At least until recent times.

If

slavery was wrong, and unjust, and despicable, and it was, the

North answered it with equal outrages. Whatever three quarters of a

million Americans suffered and died for, it was not for Black Civil

Rights or true Negro enfranchisement, as little changed for a

majority of them for one hundred years. Initially the Republicans in

power only wanted to disenfranchise Whites and allow Negro

enfranchisement for the freedmen in the South, not in their own

states. They wanted to make the South attractive to northern Negroes,

and when that failed, they conspired to purchase the Dominican

Republic to send them there. After that failed, they abandoned

Blacks and their issues for almost a century, leaving them to the

discretion of each State... recognizing the impossibility of usurping

States Rights.

Justified by inflamed hatreds and self-righteous

intolerance, the war was really about the North's military

subjugation of a rising economic threat in the South; the biggest

sham, the worst case of government bullying in our history.

Tragically,

the country had to relearn, by spilling a great amount of blood, that

two wrongs do not make a right. Abolition was a short-sighted

campaign, with no clue about implementation. Freedom for the

slaves brought all of the suffering and displacement and persecution

that the Southerners feared, in the North as well as the South, some

of which is still evident up to this very day. Many Northerners

suffered as well, and lost loved ones in order to purchase African

American Emancipation. And when they saw the reality of the

war, and its results, and its cost in human lives, not a few

concluded that the Negroes had incurred a debt they could never

repay.

This

did nothing to improve race relations in the North or the South. The evils of slavery were eclipsed by the wholesale

slaughter of our young men and the invasion and destruction of a

large part of the deep South. And today America has forgotten the price paid in human sacrifice for the sins of our founders. New resentments, fresh indignation

flows from a fountain of racial distrust, in every corner of the

country.

So

many had perished. And for what? Incredibly, as late as the Great Depression,

ex-slaves remembered the plantation times quite charitably, as they

had lived so much better then. It seemed the well-intentioned Yankees

had won them an inferior kind of “freedom.” That is because the

war was never about them. Blacks were pawns in a ruthless power grab,

which worked in many ways for the North. Slavery justified a war which led to Emancipation. And under-prepared, unfinanced freedom would guarantee decades of social unrest and economic

plight in the former Confederacy, thus insuring the stability of Northern

economic power. Reconstruction would allow Northern investors to

gobble up properties, factories and farms, and to commandeer Southern

banks and whole economies, and systematically take advantage of widespread economic

vulnerability. This predation on the devastated became a predictable

strategy in future world wars. War became the great cash cow for

American capitalists, who cut their teeth on their own people, and

soon sharpened them on the Spanish, and then all of Europe.

Lee

had been right. He had been right about States Rights, still

championed today, and the legality of secession, as well as his

doubts and suspicions about Northern motives. The Negroes were soon

forgotten, left to their own abilities, and the Northern banks

orchestrated a series of depressions and recessions which justified

their contrivance of a entrepreneurial brier patch... a central bank,

eventually the Federal Reserve Bank and the Federal Reserve Board,

private capitalist institutions with no accountability, then

abandonment of the gold standard, and then the Great Depression,

which facilitated the financial encumbrance of the masses, and a

great, unprecedented concentration of wealth... in the North and

beyond. By eliminating most competition, the Civil War made all of

that possible.

After

that, Americans were just a little bit afraid of their own

government. And silent Northern-based powers have run the country,

unchallenged, ever since. Ruby Ridge, Waco... the Mueller

Investigation, all prove that the United States Government is still

ruthless, easily threatened, and the spirit of the American people is

forever kept in check.

Ironically,

Mariah Syphax's sons, sons of former Custis slaves, far better educated

than most Blacks of the time, were some of the first freedmen to be

employed by the U. S. Government, and worked in various government offices

in Washington D. C.. Their ability to perform satisfactorily in such

prestigious and coveted jobs speaks volumes for the kind of

environment they were raised in. They had no doubt been some of the

Negro children illegally educated by Mrs. Custis and her daughter,

right in the Custis home. The Syphaxes became civic leaders and

proponents of public education, and Civil Rights, for generations. If

only the Custis's vision of Negro acculturation had been allowed to

spread and prevail, many more would have realized the Emerican dream.. and

sooner, and a great deal of tragedy might have been

avoided... and perhaps for a century.

Custis

Lee fought for years to recover his family's plantation. His mother

had died trying to shame the United States Government into admitting

their violation of her property rights. No other Confederate soldier

had been penalized and violated as much as Robert E. Lee, even having

his very land and possessions taken away. Regardless of its

illegality, many Northern leaders relished in the revenge they saw in

the Lee's losses, and refused them any compensation or satisfaction.

In fact Mary had sent the tax money in question during the war, and

they had refused to accept it from a third party. She made one

last visit much later and saw the defacement and government

improvements, and thousands of tombstones, and never came back. The

great-granddaughter of Martha Washington died without a home of her

own, disgraced, branded forever as a traitor.

But

Custis Lee, like his father, would live and die on principle. He took

his mother's case all the way to the U. S. Supreme Court and won his

claim against the U. S. Government. Afterwards he admitted that the Arlington Cemetery

should remain, as even fellow Confederates were now buried there, and

took a monetary settlement instead.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave your comments... but please be respectful.